At CDO School, one of the fundamental steps in our Playbook is making bets on where to position Design to win and with whom, not as a zero-sum game, but in how design can successfully bring the most value to customers, the company, teams, and individuals.

When you lead Design, the most significant shift is knowing that most of your colleagues don't think about design as a craft or practice. They think about it as a group of people with specific skills and capabilities with a budget… essentially a big pile of "features". Yes, they want to know how these "features" help customers, but they really want to know how those "features" help them.

If you've ever read "Crossing the Chasm" by Geoffrey Moore, one of the basic theories that Moore shares in the book is that there is a gap between early adopters of a product and the larger, more skeptical mainstream market. When you lead Design, it's basically the same thing.

Innovate with Sidekicks and Sell to Champions

Every place I've worked, there have been early adopters of Design, but most of my colleagues were skeptical. It was my job to place bets on which partners were the early adopters, intentionally design new solutions with them, and collaborate with them to build business cases to win over the skeptics. I call those early adopters Sidekicks.

I then separate skeptics into two categories; Champions and Challengers. Champions are people who have power and influence inside the company, but want evidence that something works before putting their energy behind it. Once they're convinced, it's a hot damn moment. They'll advocate for Design not just with words, but with time and money too.

Here’s a video describing this concept.

In my experience though, design leaders aren't intentionally trying to work with Sidekicks and Champions. Instead, they spend most of their time and energy trying to convince Challengers that Design is real, necessary, and good. Time and time again, I see this approach fail.

Why? Challengers aren't early adopters.

They show little demonstrable evidence that they want the change they talk about. Instead, Challengers are late adopters. They only fall in line once someone else with power (hint: Champions) start getting the benefits of Design because they don't want to be left behind.

There are great solutions for Challengers though. They're the tried and true processes or tools that really don't bring new solutions, but reliable ones. Design Systems, for example, are perfect for Challengers. They get value, customers get value, and design leaders can prioritize bigger bets for change in other areas. Win-Win.

If you want to become a Director or VP or CDO, this stuff is part of the gig and it's completely learnable. And you can do it without giving up your moral values or ethics. In fact, learning it and practicing it before becoming the exec is the best way how to keep your morals and ethics.

TLDR; When you lead Design, Design is the product. Great leaders make bets on where to position Design to win and with whom, not as a zero-sum game, but in how design can successfully bring the most value to customers, the company, teams, and individuals.

Why Good Design Isn't Enough

In my time creating and leading in-house teams, the honest truth is success has been mixed. After working with other product and design leaders, I’ve noticed they’ve had similar results. A mixed bag of wins and losses, but predominantly, outcomes that didn’t move the needle much either way.

For a long time, I’ve been examining the difference between design teams that have become crucial to their company’s success and teams that are thought of as “nice-to-have” but not necessary. There are countless factors at play (business models, industries, markets, regions, public vs. private, stage of company, etc.) that come into play.

It would be difficult for any economist or academic to pull together these factors in a way that shows causal reasons. Still, I see something happening that separates these teams. While this is entirely anecdotal, here's the pattern I see:

- The design teams that executives believe are crucial to the company’s success intentionally and consistently calculate (and recalculate) how and where design fits within the company. They repeatedly deliver new value to customers and the business again and again.

- The design teams that are considered to be “optional” wait for the company to tell them where design fits within the company. They repeatedly deliver, but not in a way that creates new value.

It’s a pattern I’ve thought about for a long time, and it’s taken me almost as long to explain what separates these teams. Here’s a framework I’ve developed to explain how design teams calculate (and recalculate) how and where design fits within the company. If you’re a design org leader, this framework may significantly change how how you lead your team.

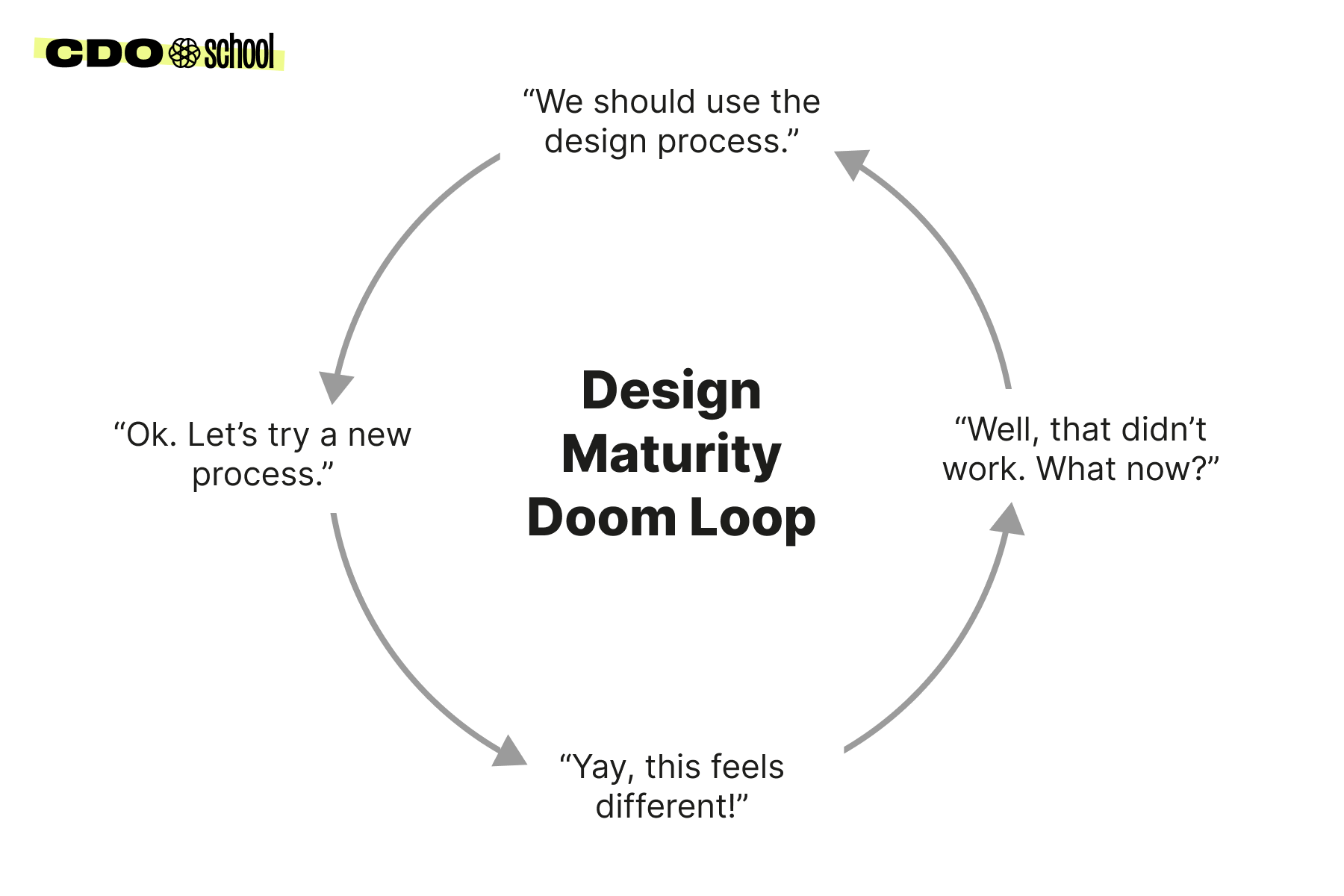

When Design gets stuck

Imagine you're playing a video game where you keep falling into the same trap over and over again. Every time you try to get out, you fall back in, and it feels like you're never going to make progress. That's what a "doom loop" is like.

The term "doom loop" was made popular by Jim Collins, in his book "Good to Great." In it, he talks about how some companies get stuck in a doom loop. As Collins writes, a doom loop happens when people make decisions to fix problems fast, but those solutions don’t address the real issues, so the problems keep coming back again and again. A doom loop is this cycle where every fix leads to more problems, and it feels like you can't break out of it.

In my experience, the teams that stagnate are stuck in doom loops. They have likely made some progress in delivering value early on, but that progress has stalled. As a result, they’re under more and more pressure to provide more value, they’re faced with more skepticism about their judgment, and worse, they turn inwards and question their ability to get the team unstuck.

In my experience, I see three ways design teams consistently try to get out of the doom loop:

- They advocate for “better” design

- They advocate for more resources

- They advocate for DesignOps and Design Systems

While each of these approaches are critical to raising the maturity level design, none address the elephant in the room: effectively changing the minds of those with the power and influence to make business decisions. These approaches do not help teams escape the doom loop.

Repeatedly delivering value requires more than just doing "better" design

When design teams are stuck in this cycle, the usual response I see is to push for more adherence to the design process. But if this were the best solution, why do designs created by that process fail to resonate with customers? Why do they fail to deliver better outcomes to the company?

The flaw in the "use the design process" approach is that keeps experienced teams from noticing the obvious: their solutions aren't working. By relying heavily on standard processes to get unstuck, design teams unwittingly limit their own ability to create something new. The longer they stay in this cycle, the more they lose credibility with their cross-functional partners and leaders.

The cycle looks like this:

This cycle typically goes like this:

- Step 1: Designers push for a design process.

- Step 2: The cross-functional team tries the new process.

- Step 3: The team feels excited because the process is new.

- Step 4: The solution has limited effect, the excitement passes, and the team is right back where they started.

- (Repeat): The cycle restarts, but over time faith in the designers goes down.

In terms of a growth curve, it looks similar to this:

Don’t get me wrong, I love a good process, but processes are overly relied upon as universal remedies. I’ve also witnessed many instances where teams used a design process well, but in the end, it didn’t translate to change. If you have strong thoughts about SAFe or Lean, you know what I mean.

I believe a fresh perspective is required to break free from this loop.

It’s more than having more resources

Another common approach is to increase the number of people on the team. Simply boosting numbers doesn't translate to delivering new value. Increasing numbers often helps deliver value that’s already known.

The problem with the "more designers" mantra is its vagueness. If I ask ten designers from a team about their definition of great design, I get ten different answers. Such variance muddles the perception of design for leadership. Adding more designers could be costly and risky without clear value addition. Teams that are delivering more value are not doing so by multiplying voices. They harmonize the voices they have.

It’s more than Design Systems and DesignOps

This is a bit nit-picky, I’ll admit. I love me a good Design System and DesignOps teams are freaking magic. While both are vital components inside some design organizations, they aren't cure-alls for every company. Design Systems and DesignOps teams help Design Orgs multiply the value of design, but inherently, they don’t create value on their own.

Again, I firmly believe in both, and the people that do this work are incredibly important, but neither don’t get teams out of doom loops.

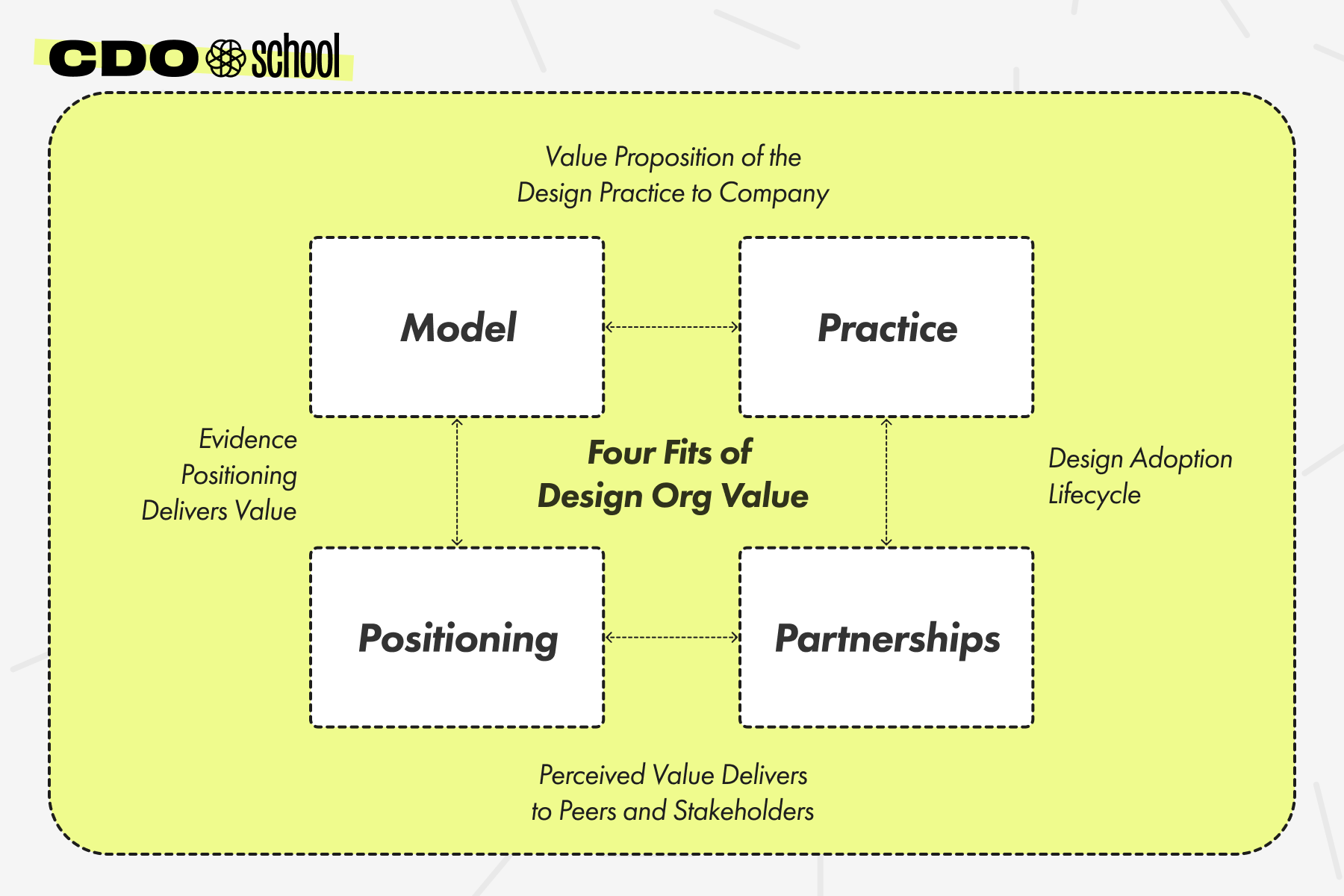

Introducing the Four Fits for Design Org Value

Another concept Jim Collins introduced was “the flywheel effect.” This concept describes how success is achieved when a consistent effort is placed in a series of small, connected actions that accumulate over time. When I spend time with design teams that are repeatedly creating new value, they are doing this exact thing.

These design teams are making bets on where to position Design to win and with whom, not as a zero-sum game, but in how design can successfully bring the most value to customers, the company, teams, and individuals. It’s a flywheel approach to running a design team.

The goal of this flywheel is to help the leaders who run design organizations consistently examine how the Design Org fits within the Company across four critical dimensions.

- Model ↔ Practice Fit

- Practice ↔ Partnerships Fit

- Partnerships ↔ Positioning Fit

- Positioning ↔ Model Fit

Here’s a visualization of the Four Fits of Design Org Value:

Model ↔ Practice Fit

A Design Team is a solution to a company problem, and that problem is often based on the business model and strategy. If you know the concept of product-market fit, this is how we examine how the design practice fits the business model and strategy.

Practice ↔ Partnerships Fit

The second fit is how Design Practices are built to fit with cross-functional and stakeholder partnerships. It’s not enough that we are advocates for customers. Our work has to help our partners as well. The degree to which we support our partners varies depending on the focus of our practice.

Partnerships ↔ Positioning Fit

In Marketing, Positioning refers to the place a brand occupies in the customers' minds and how it is distinguished from the competitors' products. Using this same concept, positioning refers to the place that Design occupies in the minds of our peers, colleagues, and stakeholders and how design is distinguished from other skills/teams at the company. Here, we continuously examine how the power dynamics work inside our companies so we can move peers and stakeholders from skeptics to adopters.

Positioning ↔ Model Fit

Lastly, the business model and strategy influence how design should be positioned inside the company. Here, we want to validate our positioning by gathering evidence that it’s working.

The four fits are essential to maturing Design, thus elevating Design's business relevance and value. These fits are interconnected; changing one affects the others. As the fits evolve, a holistic review and adjustment of your playbook is necessary. I will dedicate a post to each of these fits and how you can use our playbook to mature these four fits.

There are three extremely important points I want to hammer home throughout these posts:

- You need to find four fits to grow the value of a design org inside your company.

- Each of these fits influences each other, so you can’t think about them in isolation.

- The fits are constantly evolving/changing/breaking, so you have to revisit and potentially change them all. This is the purpose of the CDO School playbook.

I will show you examples of the framework through my failures and successes. The series will roughly go in this order:

- Model ↔ Practice Fit

- Practice ↔ Partnerships Fit

- Partnerships ↔ Positioning Fit

- Positioning ↔ Model Fit

- How The Four Fits Work Together

Finding Business Model - Design practice fit

The road to Design Maturity doesn't start with Design.

In the introduction to this series, I emphasized that better Design is not the sole factor for figuring out where and how design plays a vital part in a company's success.

There are actually five essential elements required to examine the first of these fits, the Model-Practice Fit:

- Understanding the business model.

- Understanding the practice (people, process, operations, budget, etc.)

- Establishing early hypotheses about the fit of the design practice and the business model.

- Understanding the practical implications of achieving Model-Practice Fit in reality, not just in theory.

- Identifying strong indicators of finding Model-Practice Fit.

The wrong way to do it

In 2011, when I joined Electronic Arts (EA) to lead a new team of designers, program managers, and front-end developers, I was also a part of the leadership team for a newly formed organization at EA called the World Wide Customer Experience team. After assembling my team, I recall thinking:

"I can't wait to demonstrate how we can build exceptional products and services because that's what they asked us to do."

Although this mindset may seem reasonable if you have been in a similar position, it is flawed. I assumed that our team was the solution to their problems, essentially putting the cart before the horse.

What I should have done instead is focus on understanding the challenges and needs of my colleagues as they worked towards improving the experience for EA's customers. I made the common mistake of assuming that my colleagues wanted us to decide for them.

This is why I struggle with the term "Design-Led Strategy." While I understand that it refers to a practice and even a philosophical approach, my colleagues often interpreted it as "Everyone Follows the Design Team." Although this interpretation may make sense to some, language matters, and the way we word things impacts our perception and understanding.

A better way to find the Fit between the Business Model and the Design Practice

During my second stint at EA, I joined the IT organization. Our task was to develop a completely new catalog of products and services to support Employee Experience. This experience was akin to running a startup within the company.

Fortunately, I had learned some valuable lessons along the way. Instead of focusing solely on what we would be creating, we shifted our focus to understanding the business model of EA and the IT organization.

We examined four key elements:

- Who: We identified several teams eager to collaborate with us. Understanding the power dynamics and influence that each team had within the company was crucial. We initially focused on conducting experiments that would maximize value without causing significant damage if the experiments went wrong.

- Budget: Each new product had different funding sources. If the budget came from IT, we used a traditional Product Development approach. If the budget came from outside our team, and another department paid for the work, we used a more traditional agency or consulting model. Why? Because we considered this as the first phase to gaining trust with that team before trying to convince them, a fully formed Product Development approach would be the best way.

- Motivations: We assessed whether the teams were trying to assist a specific audience that held significant value and importance to the company.

- Problem: We evaluated whether the problem could be easily addressed from a technical standpoint.

Using these criteria, we discovered an ideal testing ground to determine the fit between the business model and the design practice.

One example of this fit was observed when we partnered with the VP of Talent Acquisition:

- Who: The VP of Talent Acquisition

- Motivations: To attract top talent to EA while reducing employee turnover costs.

- Problem: Candidates had to use multiple systems and tools to communicate with the recruiters, hiring managers, interviewing teams, and IT systems. It was a mess.

- Budget: No direct budget allocation. They relied on IT to cover the expenses, which gave us some leverage to drive the conversation.

Based on these definitions, the team began considering potential solutions. Bill Bendrot, Jesse, and a few others collaborated to create a tool called Interview Sidekick. It marked the initial step towards developing a larger platform that would eventually replace EA's intranet. Despite being the same product with the same underlying architecture, Interview Sidekick was a simple web app that:

- Helped candidates understand what to expect during the interview phase, aiding in a smoother process and allowing candidates to focus on the content.

- Established personalized connections with candidates, with all communications at each step of the process in one place.

- Boosted candidate engagement, fostering a connection to EA's culture and providing insights into working at EA (answering the question "why EA?").

- Differentiated EA's interview process from that of other companies, giving EA a competitive advantage in attracting talent.

Although the app seemed simple, teams within EA had never experienced this type of product before. It helped the Talent team solve business problems and allowed us to adapt our practice to accommodate budgetary constraints, resource limitations, and cost drivers. Even today, some 8 years later, Interview Sidekick remains the standard way new candidates interview at EA.

This brings us to the concept of practice fit. We identified four main elements that were crucial to define:

- Initiatives: The key tasks and activities related to product work that the team was working on, expected to work on, or hoped to work on, such as which development approach, phases, tools, etc.

- Process: The rituals, norms, and agreements of the team developing the product, such as the principles, workflows, communications, and frameworks.

- Resourcing: Identifying and scheduling the exact people who would be part of the product development team

- Capabilities: The key skills, levels, roles, and responsibilities the team provides.

These were the elements we identified:

- Initiatives: Creating the initial v.1 product for Inverview Sidekick, which included scheduling the onsite interview, tips to prepare for the interview, communicating status updates with the candidate, and providing next step instructions post-interview.

- Process: We utilized a Design Sprint approach, a new concept that required early signals of if, how, and where it was working. We developed the product over three months using two-week sprints.

- Resourcing: The initial work was done “off-budget”, meaning we found resource availability to create an MVP in 5 days without proposing a formal budget. The goal was to get enough signals from the MVP to become part of the business case to fund the full product development.

- Capabilities: Front-end engineer, Sr. Designer with a Master's in HCI, software architect, project manager, Sr. Recruiter, and QA tester.

These hypotheses play a crucial role and will be explored further in future posts of this series as they inform and deeply impact the other components of the framework: Partnerships and Positioning.

The Realities of Finding Business Model - Design Practice Fit

The reality is that finding Model-Practice Fit is rarely straightforward.

It often takes multiple iterations to identify a fit that works. The process begins with understanding the business model and strategy, not by prioritizing the business aspect, but rather as a reference for the signals that those with a business-first mindset are seeking. This iterative cycle involves creating an initial version of your practice, identifying who benefits from it, and then refining both the model and the practice. It is an ongoing process that becomes easier to comprehend over time.

The same applied to our work on Interview Sidekick. We initially laid out our hypotheses, but as we delved deeper, we discovered that our practice was delivering value to various aspects of the business. We achieved significant wins in enhancing IT's reputation, staying on budget, increasing top candidate closure rates, and improving NPS.

Upon realizing these outcomes, we refined the category, the target audience, the problem, and the motivations based on our actual observations. The second version looked like this:

- Who: VPs running operational, cost-center teams who 1.) owned a budget and 2.) were struggling to solve their problems at scale. HR, Sales, Accounting, Customer Support, DevOps, etc.

- Motivations: To increase productivity while maintaining relative costs, and be seen as change-makers within the organization.

- Problem: Members of their teams were used to consumer grade applications and software. When their tools and apps were slowing them down or causing high frustration, they’d use outside, third-party tools to get their job done - creating security and legal risks.

- Budget: No direct budget allocation. They relied on IT to cover the expenses, which gave us some leverage to drive the conversation.

We saw these teams as early-adopters/testers. We could introduce new ways of working, digital solutions, and have discretion over the approach. When these tests went well, they became case studies to scale our approach to other teams.

The refinement did not stop there. About a year later, we experienced another major shift, which I will discuss in future posts.

The Model-Practice Fit is Not Binary

The iterative cycle of Model-Practice Fit leads us to another important point:

Model-Practice Fit is not a binary concept, nor is it determined at a single point in time. A more accurate way to perceive Model-Practice Fit is as a spectrum ranging from weak to strong.

When thinking about Model-Practice Fit as a binary concept, it implies that the business model and design practice remain static. However, in the real world, change is constant. Therefore, we should consider changes to the business model as the focal point for altering our practice.

In my career, I’ve seen three primary ways in which the business model changes:

- Senior Leadership turnover

- Regulatory pressure

- Overall business evolution

The first two changes happen quickly, without much notice, and we can only respond when they happen. The third one though, is a longer process that Design Leaders can play a more proactive role in influencing, but are never the sole party responsible for the change.

Signals of Model-Practice Fit

If Model-Practice Fit is not binary, how can we determine if we have achieved it? While there has been some discussion on this topic, most of it does not reflect reality.

In almost every case, it is necessary to combine qualitative and quantitative measurements with your own intuition to understand the strength of Model-Practice Fit. Relying on just one of these areas is akin to trying to perceive the full picture of an object with only a one-dimensional view.

So, how do we combine qualitative, quantitative, and intuitive indicators to gauge the strength of Model-Practice Fit?

1. Qualitative:

Qualitative indicators are typically the starting point for measuring Model-Practice Fit, as they are easy to implement and require minimal customer feedback and data.

- Employee Satisfaction

- Partner Satisfaction

- Team Health Scores

To gain a qualitative understanding, I prefer using Net Promoter Score (NPS). If you are genuinely solving the audience's problem, they should be willing to recommend your product to others.

The main downside of qualitative information (compared to quantitative data) is that it is more likely to generate false positives, so it should be interpreted with caution.

2. Quantitative:

There were three initial quantitative measures to understand Model-Practice Fit: Budget Adherence and Utilization.

- Budget adherence

- Velocity

- LOE Accuracy

You’ll notice here, that we’re not talking about Product-Market Fit. That’s work that was done within the Product Team. Model-Practice Fit is ensuring that the resources, processes, and skills within the design team are fitting to the business needs.

3. Intuition:

Intuition is a gut feeling that is difficult to articulate. It is challenging to intuitively understand whether Model-Practice Fit has been achieved unless you have experienced situations where it was absent and situations where it was present.

Here’s a vibe that time and time again has shown me that Model-Practice Fit is strong:

When you have strong Model-Practice Fit, it feels like stakeholders are pulling you forward into their decision-making meetings rather than you pushing yourself into them.

The Key, Practical Points to Help You Find Model-Practice Fit

If you haven’t noticed yet, many of the things we teach here are structured activities to gain new insights into how you can learn to find your four fits.

The key questions that it’s important to have answers for are:

- How does design support or enhance the business in the direction it’s going?

- How does design support or enhance the current focus on the business?

- What challenges is the business facing that the design practice is THE ideal solution?

Finding Design Practice - Partnerships Fit

Instead of thinking about partnerships as a separation of skills and responsibilities, think about them in a similar way that customers adopt new products and services. Some partners are early adopters, while there are others who adopt late – often begrudgingly.

In our previous lesson about Model-Practice Fit, we explored the importance of aligning design teams with the business models and strategies for which they are working with/in. However, even with great Model-Practice Fit, the level of maturity in the partnership plays an outstanding role in how quality is defined.

In my experience (and hearing from others), every design leader will be faced with situations where cross-functional partners operate at different levels of maturity, prioritize operations over innovations, or make decisions based on gut feel rather than business 101.

This brings us to our second fit: Design Practice-Partnerships Fit.

There are five essential elements required to examine Design Practice-Partnerships Fit:

- Understanding who your partners really are (beyond the org chart)

- Understanding your partners' perceptions of success

- Understanding the practical implications of achieving Practice-Partnerships Fit

- Identifying strong indicators of having Practice-Partnerships Fit

- Recognizing that Partnerships run on a spectrum, and the need for design maturity will be different with different partnerships

The wrong way to do it

When I first moved into Senior Management (my first time at EA), I was hired to lead a team of designers, researchers, front-end developers, and program managers. We were responsible for creating in-house enterprise software as it related to Customer Support. We worked along side a brand new engineering team as well, and that partnership was solid from the start.

I leveraged all the skills I had learned at Apple, and began to bring these into the design practice at EA. We had what I thought was a solid design practice: strong processes, talented designers, and a clear vision for improving the user experience.

However, we kept running into resistance from our partners in HR, IT, and frankly, my boss.

I thought we were doing our job well by advocating for users, testing, validating, and creating polished designs. We did this because this is what I believed I was asked to do. After all, my boss even said, “EA needs what you did at Apple.”

What I failed to understand is that I was no longer surrounded by the same types of partnerships, skills, and beliefs that I had at Apple. The team I was leading was five steps ahead from what my new partners at EA had experienced before. As a result, some partners were confused or hostile, while others were energized and excited.

I was treating design as a binary, one-size-fits-all approach and could not see where this approach was working and where it wasn’t.

I had fallen into the trap of thinking that our only job was to create "good design," rather than understand that another job was to help our partners succeed. I had fallen into the trap of believing my way was the right way to succeed, and that failure led to predictable results: delayed projects, missed opportunities, arguments, compromised designs, and frustration all around.

A better way to find Practice-Partnerships Fit

Later in my career, during my second time at EA, I took a radically different approach.

Instead of thinking about partnerships as a separation of skills and responsibilities, we started thinking about them as relationships we needed to nurture and strengthen. We started thinking about them in a similar way that customers adopt new products and services. There are some who are early adopters (they follow the new trends), while there are others who adopt late – often begrudgingly.

This time, we examined four key elements:

- The Range of Success Metrics: We started by understanding what success looked like for each functional team. For Engineering it was velocity, technical debt reduction, maintainable code, reasonable sprint commitments. Game Studios were looking for feature delivery, consistent brand experience, and new competitive advantages. For HR, there was a strong focus on improving employee communications and perception. And for Customer Support, it was always cost savings, reduced ticket volume, and improving satisfaction.

- Perception of Value: As they say, perception is in the eye of the beholder. Despite many of the teams we worked with having stated goals and metrics, quite often the senior leader of those teams made decisions that were personal. The senior HR leader for example had “owned” EA’s intranet for years. No amount of data letting them know that their tools were unliked and weren’t be used convinced that leader that they were making poor decisions.

- Flexible Engagement Models: I have never seen or have been successful in having a single engagement model for how partners engage with the design team. IMO, the conversations on whether to work like an agency or be embedded leaves out two important factors: money and maturity. In the past, I’ve worked at several companies like EA where the design team worked on projects that came out of my boss’s budget as well as projects that came out of other departments. How a project or initiative is paid for greatly defines the engagement model. Many times, I’ve worked with Senior Leaders who needed help from the design team, but whose organizations did not need world class results in order to meet their goals. In this sense, it’s important to meet the appropriate level of maturity as it relates to the context.

- Value Exchange: We clearly defined what each partner would get from the relationship and what they needed to contribute in order to get that value. Our focus was to clearly articulate the reciprocal flow of expertise, resources, and benefits between teams… write them down, and communicate them frequently throughout the project. By highlighting this give-and-take between teams, and recognizing both tangible deliverables and intangible benefits, it helped us assess and communicate the pros and cons of each proposed change.

One example of this fit was observed when we partnered with the VP of Customer Experience:

- Who: The VP of CX

- Team Success Metrics: To reduce bill-back costs to game studios

- Perception of Success: CX is the hero of the story

- Engagement Model: As the work was coming from their budget, we would act like an internal agency. They owned the prioritization, goal definition, etc. We owned the delivery, would deliver within their scope, and clearly inform them on what they would (and wouldn’t) be getting.

- Value Exchange: We would provide key skills and capabilities. Our skills and capabilities were only as good as their clarity on goals, priorities, and budget.

Team Success “Metrics”

In working with the VP of CX, we identified several specific challenges that influenced how we structured our partnership:

- Time constraints: The CX team was under pressure to reduce costs quickly, which meant the priority was to deliver value in shorter cycles

- Resource limitations: Like many support organizations, they had limited resources, primarily in building digital products and budget restrictions

- Technical legacy: The existing support systems were complex and interconnected, and not easily replaceable

- Business pressures: Each game studio was pushing back on support costs

- Organizational dynamics: The CX team needed to be seen as proactive problem solvers

Perception of Success

What made this partnership particularly interesting was the importance of perception. While the stated goal was reducing bill-back costs to game studios, we quickly learned that the VP of CX needed to be seen as the hero of the story. This meant:

- Ensuring the CX team got credit for improvements

- Creating narratives around cost savings that the VP could share upward

- Positioning changes as CX-led initiatives

- Making sure game studios saw CX as a strategic partner, not just a cost center

Engagement Model

Based on our understanding of both the metrics and perceptions of success, we customized our engagement model. Since the work was funded from their budget, we operated like an internal agency:

- They owned prioritization and goal definition. We owned delivery and execution

- We adapted a Service-Level Agreement format, a traditionally used document that defines the level of service expected from a vendor, laying out metrics by which service is measured, as well as remedies should service levels not be achieved. It is a critical component of any technology vendor contract.

- We provided clear scope boundaries upfront related to the priorities. If they changed the priorities, we informed them of the consequences

- We established regular check-ins using their preferred format. In this case, they operated using two-week sprints, so we incorporated two-weeks sprints of our own for the engagement.

This model worked because it:

- Gave the CX team control over their budget

- Allowed us to define quality standards within their budget, timeline, and goals.

- Created clear accountability on both sides. Matched their maturity level and needs.

Value Exchange

With the engagement model established, we created explicit agreements about value exchange:

From the Design team:

- User research via interviews and observations

- Prototyping in the browser

- Rapid usability testing

- Delivering

From the CX team:

- Clear goals and priorities

- Dedicated budget

- Access to support staff

- Decision-making authority

- Timely feedback

This clear value exchange helped both teams understand their responsibilities and prevented common partnership pitfalls like scope creep or unclear decision-making.

The Reality of Finding Practice-Partnerships Fit

Just like Model-Practice Fit, finding Practice-Partnerships Fit is an iterative process. Our work with EA's Customer Experience team provides a perfect example of this reality.

Initially, we thought our primary partnership would be just with the CX leadership team. After all, they were the ones with the budget and the stated goal of reducing costs. However, as we dug deeper, we discovered a complex web of necessary partnerships:

- Game Studios (who were being billed back for support costs)

- Support Agents (who used the tools daily)

- IT Infrastructure (who maintained the systems)

- Analytics teams (who tracked costs and performance)

Each of these partnerships required a different approach because each team had different success metrics, perceptions, and ways of working:

With Game Studios, we:

- Showed how support cost reductions wouldn't impact player satisfaction

- Created transparency in how costs were calculated

- Built feedback loops to understand their pain points

- Demonstrated the value of preventive support measures

With Support Agents, we:

- Involved them in early design decisions

- Created processes that respected their expertise

- Built tools that made their jobs easier

- Showed how improved efficiency benefited them

With IT Infrastructure, we:

- Aligned with their technical standards

- Participated in their planning cycles

- Created documentation they could maintain

- Respected their existing systems and processes

With Analytics Teams, we:

- Developed shared metrics for success

- Created dashboards that served multiple needs

- Built trust in the data collection process

- Established regular review cycles

Design Practice – Partnership Fit is Not Binary

Like Model-Practice Fit, Practice-Partnerships Fit exists on a spectrum. In our CX partnership work, we observed three primary partnership states that evolved over time:

1. Transactional

Initially, many game studios viewed CX purely as a cost center:

- Interactions focused solely on cost reports

- Minimal collaboration on solutions

- Success measured only in cost reduction

- Limited strategic input

2. Collaborative

As trust built, partnerships evolved:

- Studios began sharing player feedback earlier

- Joint planning for major game launches

- Regular informal communication channels opened

- Growing alignment on player satisfaction metrics

3. Integrated

Eventually, with some studios, we achieved:

- Shared success metrics combining cost and player satisfaction

- Deep understanding of each studio's unique challenges

- Proactive problem-solving before launches

- Full strategic alignment on player support strategy

Signals of Practice-Partnerships Fit

How do you know if you have strong Practice-Partnerships Fit? In our CX transformation, we looked for these key indicators:

Qualitative Signals

- Game studios began including CX in pre-launch planning

- Support insights were sought during game development

- Studios defended support budget to their leadership

- Informal communication increased between teams

- Shared vocabulary around player support emerged

- Studios confidently presented support strategies to their stakeholders

Quantitative Signals

- Reduced support ticket volumes

- Increased first-contact resolution rates

- Faster problem identification and resolution

- Higher studio satisfaction with support

- Improved launch readiness metrics

- Decreased escalations and conflicts

Intuitive Signals

The strongest signal was when game studios started presenting their support strategies to their leadership without needing the CX team in the room – not because they were excluding CX, but because they truly understood and believed in the support approach. They had become genuine advocates for player-centric support, not just cost management.

Key Practical Points to Help You Find Practice-Partnerships Fit

To build strong Practice-Partnerships Fit, focus on these key questions:

- How does your design practice make your partners' jobs easier? (For CX, we made it easier for studios to manage support costs while maintaining quality)

- What are your partners' primary measures of success, and how are you helping them achieve those? (For studios: launch success, player satisfaction, cost management)

- Where are the friction points in your current partnerships, and what changes in your practice could reduce that friction?

- How can you adjust your practice to meet partners at their current level of design maturity?

- What value exchange model makes sense for each partnership?

Here at CDO School, we help you develop these partnerships through several key frameworks, step-by-step quick guides, and of course, our Toolkit.

Finding Partnership - Positioning Fit

The email arrived on a Thursday afternoon, just as I was wrapping up my first month back at Electronic Arts, this time building a team within IT. "We need these intranet mockups by Friday. Nothing fancy, just make it look good." I stared at my screen, feeling that familiar knot in my stomach. Here we were again—the design team relegated to last-minute cosmetic touches, our expertise reduced to "making things pretty."

This moment became a turning point in how I understood organizational partnerships at EA. In just that first month, I'd encountered the full spectrum: from teams that maintained rigid control and saw design as purely executional, to those eager to explore new approaches that could transform the employee experience. Learning to recognize and work with these different partnership types didn't just help us survive—it became the foundation of our success.

The Three Partnership Types

Through both of my experiences leading design at EA, I began to see clear patterns in how different teams approached their relationship with design. Each type required a different strategy, and understanding these differences helped us navigate the organization more effectively.

I've previous written about finding Executive Champions at work. As a refresher, there are three partnership types for which I've had to give energy to:

- Champions: influential partners who can help drive scalable adoption of design

- Challengers: influential partners who may be skeptical of design

- Sidekicks: partners willing to experiment with something new and willing to forgive if the experiment doesn’t go as planned

Challengers: High Power, Low Flexibility

The HR team exemplified what I came to think of as a "Challenger" partnership. They held significant organizational power but showed limited willingness to embrace new approaches. With the intranet project, despite mounting evidence of declining employee engagement, they remained committed to their established ways of working.

Working with Challengers taught me to focus on excellent execution within constraints. While we couldn't drive strategic change directly, we could still deliver value through careful implementation. More importantly, I learned that Challengers often change their approach not through direct persuasion, but by seeing successful results elsewhere in the organization.

Champions: High Power, Evidence-Driven

I found that Champions operated differently. These executive-level partners had the power to drive significant change but needed to see evidence before fully committing. They were willing to experiment but required concrete results before scaling new approaches. Once convinced, they became powerful allies, often helping to influence more resistant Challengers through their success stories.

Sidekicks: Lower Power, High Trust

The Talent Management team showed me what a "Sidekick" partnership could achieve. While they had less organizational power, they trusted our expertise and were willing to try new approaches. These partnerships, though smaller in scope, produced the case studies and evidence needed to convince Champions and, eventually, Challengers. Our work on Interview Sidekick demonstrated how these partnerships could create transformative results that influenced the entire organization.

The Multi-Mode Reality

Through these experiences, I developed what I called our "multi-mode model." Instead of trying to transform every partnership into the same ideal state, I learned to optimize our approach based on each partner's type and potential for evolution.

With Challengers like the HR team, I focused on:

- Delivering exceptional execution within constraints

- Building credibility through reliability

- Maintaining readiness for when they saw success elsewhere

With Champions, my emphasis was on:

- Creating clear evidence of impact

- Scaling novel, but proven approaches

- Documenting success metrics

With Sidekicks, I prioritized:

- Innovation and experimentation

- Building compelling case studies

- Creating examples that Champions could reference

Managing Partnerships on a Spectrum

I discovered that success wasn't about trying to transform every Challenger into a Champion, but rather about working effectively with each type. Here's what worked for me:

- Identify Partnership Types Early

- Assess organizational power dynamics

- Evaluate openness to new approaches

- Understand political relationships between partners

- Deploy Appropriate Strategies

- For Challengers: Focus on execution excellence

- For Champions: Emphasize evidence and metrics

- For Sidekicks: Enable innovation and experimentation

- Create Success Networks

- Use Sidekick successes to influence Champions

- Let Champion victories influence Challengers

- Build a portfolio of evidence across partnership types

Finding Partnership-Positioning Fit in 90 Days

Based on my experience, here's how I’ve considered and implemented this partnership model over a 90 day period. If I’m in a new job, I do this in the first 90 days. If I’ve been in a role for a while, this likely won’t take 90 days. And when there’s an org change, I reevaluate the current fits.

Days 1-30: Partnership Mapping

- Map your current partnerships and their types

- Understand the influence networks at play

- Document where each relationship stands today

Days 31-60: Positioning Development

- Create specific value propositions for each partner type

- Position your team as execution experts to Challengers

- Frame your work as innovation-driven for Sidekicks and evidence-based for Champions

Days 61-90: Implementation

- Begin initiatives with your Sidekicks

- Document early wins for Champions

- Optimize execution for Challengers

Positioning Your Design Team

For in-house design teams, reading the room is everything. While conventional wisdom suggests that positioning drives perception, the reality for design teams is often reversed: your ability to read and respond to shifting stakeholder perceptions should drive your positioning decisions.

I learned that understanding partnership types was only half the equation. The other half was positioning the design team appropriately for each audience.

Positioning for Challengers

With our HR partners, I learned to position the design team as execution specialists rather than strategic consultants. This meant:

- Emphasizing our track record of reliable delivery

- Highlighting technical expertise and attention to detail

- Focusing communication on efficiency and risk reduction

- Demonstrating respect for established processes

- Using their language and metrics when discussing work

For the intranet project, I shifted from pushing for strategic involvement to positioning us as technical experts who could deliver precise implementations on time and on budget. This approach helped maintain productive relationships while we built influence elsewhere.

Positioning for Champions

For Champions, I focused on evidence-based positioning that spoke to business outcomes:

- Leading with data and measurable results

- Connecting design metrics to business KPIs

- Presenting case studies from similar organizations

- Offering low-risk pilots with clear success metrics

- Positioning design as a business tool rather than a creative service

Positioning for Sidekicks

With the Talent Management team, I positioned us as innovation partners and change catalysts:

- Emphasizing our problem-solving methodology

- Sharing emerging trends and best practices

- Demonstrating our user research capabilities

- Highlighting our ability to experiment rapidly

- Positioning design as a transformation tool

Cross-Pollinating Positioning

The real power came from using these different positioning strategies to create a network effect:

- Using Sidekick successes to build case studies for Champions

- Using Champion endorsements to influence Challengers

- Using Challenger execution wins to demonstrate reliability to everyone

The Long-Term Impact

What I ultimately learned at EA was that success in organizational design isn't about converting every partner to your way of working. It's about understanding each partnership type and optimizing your approach accordingly. While our HR partnership remained a challenging one, we excelled at execution in that partnership while building evidence of novel and unique solutions through Sidekicks and Champions elsewhere. This multi-speed approach led to broader organizational change, driven not by force but by example and influence.

To sum things up, each partnership type plays a vital role in making progress. Challengers keep us sharp on execution, Champions help scale proven approaches, and Sidekicks are the partnerships that create the kind of evidence needed for broader change. In my experience, success has come from working effectively in this multi-mode model.

Finding Positioning - Model Fit

After spending eighteen months at EA building new employee experience products, I thought we had finally cracked the code. Our Sidekicks loved working with us, Champions were advocating for our approach, and even some Challengers were coming around. We had case studies, glowing testimonials, and successful launches. I believed I was in the perfect place to ask for more headcount and resources to keep going.

Then, during our Q4 planning sessions, my boss asked a simple question: "I know you're doing great work, but I have to ask for more budget to get you what you need. To do that, I need to see the numbers. Can you show me how this ties back to revenue and costs?"

I had the answer. We had built scorecards, tracked statistical correlations, and could show exactly how our work led to good outcomes. The problem? My CIO, the person who could get us more headcount and resources, was hearing it for the first time.

In this case, I didn't meet my own expectations. Not because we couldn't prove our value, but because I had failed to get ahead of the conversation. I had the evidence, but I hadn't equipped my boss to defend my ask when it mattered most.

This is the real challenge of the Positioning ↔ Model Fit. It's not just validating that your positioning supports the business model and strategy through metrics, statistics, and math. It's proactively communicating that validation to the people who want and need to advocate for you.

Why Positioning ↔ Model Fit Matters

Positioning ↔ Model Fit is about validation through evidence, not aspiration. It's the difference between what we want design to be known for and what design is actually known for. It's the connection between the perception that design delivers business and the ability to prove it with evidence.

Without this fit, design teams can become incredibly effective at things the business doesn't value. The wrong kind of credibility is built with the wrong stakeholders at the wrong time, and without the ability to prove otherwise, are stuck in execution.

Five essential elements to examine Positioning ↔ Model Fit:

- How the business model and strategy is/isn't evolving

- How design value is currently positioned in the minds of stakeholders

- Whether that positioning serves customers and the business direction

- What evidence validates (or invalidates) the positioning

- How that evidence is being communicated in business terms

The Wrong Way to Do It

During my first stint at EA, I made two classic mistakes: I positioned the design team based on what I thought we should be, and I tried to prove our value by talking about "best practices" that meant nothing to the business.

I came from Apple, where design was central to product strategy. When EA recruited me and told me they wanted that level of design, I assumed the needed the same thing. So, I positioned our team as strategic partners who would help shape product direction. I talked about methods, processes, and analysis.

When asked to show the value we were creating, I presented user research insights, heuristics evaluation findings, and System Usability Scale scores.

The problem? I was working in a part of EA's business that was focused on operational efficiency and cost reduction; the customer support org. They needed design to help them provide better support while saving money, not reimagine everything or show them usability scores they didn't understand.

My positioning was great for Apple, but irrelevant at EA. My evidence was rigorous for my previous job, but meaningless at this one. I had failed to validate whether our positioning actually fit the business model, and I couldn't prove our value in terms they recognized.

A Better Way to Find Positioning ↔ Model Fit

During my second time at EA, I took a fundamentally different approach. I started by understanding the business model deeply, then built evidence frameworks that connected design work to business outcomes in language stakeholders already understood.

I began by examining where EA's business was heading and, critically, how they were already measuring success financially, operationally, and from the customer's perspective. Rather than focusing my efforts on establishing new measures, I recognized the cultural and strategic importance of what was already being measured.

Building the Evidence Framework

This is where my experience at Apple became invaluable. In 2009, I had been challenged to recreate the scorecards my colleagues used to track business performance. That experience taught me something crucial.

To help my colleagues understand how design connected to business, I didn't need to talk about process or devise new metrics. I needed to solve a communication gap.

I learned to borrow the categories my colleagues used to understand the health of the business and connect design outcomes directly to them. But I also needed to show how design specifically contributed to the success of the products and services we were actively working on. I developed what I now call the POKR Method, in which I established four Product Desirability Health Categories:

- Credibility = Can customers/employees trust and rely on this?

- Impact = Does this create meaningful value for them?

- Usability = Can they actually use this effectively?

- Detectability = Can they find and understand what they need?

Since we were working within an employee experience context, these categories provided us with a story framework to communicate how our positioning was working when it came to building better tools for employees.

An example of this can be described through the work we did for an internal design system called Joystick. We knew that a Design System would help us raise the quality of tools for employees and would ultimately save the company money because of it's use.

To communicate our positioning, we came up with two stories. The first was around the importance of making the design system desirable to developers. The second, communicated how our positioning with those developers was delivering on the business goal of raising product quality while reducing costs.

If developers are more aware of our design system (Detectable)

→ But we ensure it fits their current workflow (Usable)

→ They will maintain their velocity (Impact)

→ Therefore adopting more of our design components (Credible)If more developers adopt our design system (Learning & Growth)

→ They'll spend less time QA'ing browser-based bugs (Operational)

→ But still raises product quality for employees (Financial)

→ Which will therefore reduce the overall production costs (Financial)This approach was very effective in that it:

- Showed logical connections between design decisions and business outcomes

- Used language the developers and execs already understood

- Made it clear where design specifically added value

- Created testable hypotheses we could validate

Gathering the Right Evidence

With the evidence framework in place, I focused on gathering the evidence that validated both the design and business impact for Joystick.

Desirability Metrics (What we could directly influence):

- Design system awareness among developers

- Component adoption rates per team

- Developer satisfaction with components

- Number of products in production using Joystick

Business Metrics (What the company cared about):

- Development velocity (story points completed)

- QA time spent on browser-related bugs

- Employee satisfaction with internal tools

- Production costs for employee experience tools

What really proved the positioning was working though was math. We used basic statistical analysis (correlation and linear regression) to show the relationships between the actions we were taking, and the outcomes being achieved as a result.

We saw direct evidence that component adoption correlated with a reduction in QA time by as much as 30% in some cases. The development teams using Joystick not only maintained their velocity, but the products they were building received higher satisfaction scores in their use. Importantly, teams using these components were able to reduce overall production costs by an average of 15% compared to before we introduced Joystick.

This wasn't about proving causation perfectly, and there were other factors at play. It was about showing credible connections that made our positioning not just valuable, but believable. I can't understate how important believability is when it comes to change.

The Reality of Finding Positioning ↔ Model Fit

<artifact identifier="positioning-model-fit-reality-update" type="text/markdown" title="Updated Reality Section"> ## The Reality of Finding Positioning ↔ Model Fit

The reality is most design teams do not know how to instrument, track, and monitor what they do. They're not comfortable with statistics and math. It's easier for them to stick with their belief systems and best practices than it is to validate if their choices are good ones.

It's easier if business people just believed us, but I have yet to see that magically happen.

The reality of finding this fit starts with acknowledging that business people will likely never understand design the way we do, and it's our job to win anyway.

At EA, this meant I had to get comfortable with things I wasn't trained to do as a designer. I had to learn correlation and regression analysis. I had to build scorecards. I had to translate design work into financial terms. None of this came naturally, and all of it felt uncomfortable at first.

Positioning ↔ Model Fit is Not Binary

Like the other fits, Positioning ↔ Model Fit exists on a spectrum from misaligned to leading the alignment. Here are patterns I've seen within this spectrum

1. Misaligned

- Positioning serves past business model

- Evidence doesn't resonate with current priorities

- Design metrics disconnected from business metrics

2. Partially Aligned

- Some aspects of positioning serve business model

- Evidence exists but isn't well communicated

- Mix of relevant and irrelevant metrics

3. Strongly Aligned

- Positioning clearly serves strategic priorities

- Evidence validates positioning in business terms

- Strong connections between design and business metrics

4. Leading Alignment

- Positioning anticipates business model evolution

- Evidence supports multiple strategic scenarios

- Proactive validation frameworks in place

At EA, we moved from Misaligned (first stint) to Strongly Aligned (second stint), with moments of Leading Alignment during our best quarters.

Signals of Positioning ↔ Model Fit

How do you know if you have strong Positioning ↔ Model Fit? This is somewhat my own hot vibes, but this is how I've come to know.

Qualitative Signals

- Executives reference your work in strategy discussions using your evidence

- Budget conversations focus on ROI and impact, not just cost

- Partners position you to their leadership using your metrics

- New executives seek you out asking for scorecards

- Your measurement language gets adopted by business partners

Quantitative Signals

- Budget allocation increases or remains protected during cuts

- Headcount requests get approved with ROI justification

- Projects connect to strategic initiatives you helped define

- Your metrics appear in business reviews

Intuitive Signals

The strongest signal is when executives defend design's value using your evidence, your strategy maps, and your business language without you in the room. When your positioning has become their understanding of design's role—validated with proof they trust—you've achieved fit.

Key Practical Points to Help You Find Positioning ↔ Model Fit

To build strong Positioning ↔ Model Fit, focus on these questions:

- Where is the business model heading and how do they measure success? (Not where it is today, but where it's going and how they'll know)

- How is design currently positioned in stakeholders' minds? (Perception, not aspiration)

- Does that positioning serve the business direction? (Honest assessment with evidence)

- What evidence validates your positioning in business terms? (Their metrics, not just yours)

- How will you adjust as the model and metrics evolve? (Maintain measurement flexibility)

Practical Frameworks

At CDO School, we teach specific frameworks to validate positioning. Strategy Maps help us visually show the cause-and-effect relationships of objective and metrics. POKRs (Perspectives + OKRs) add an additional lens, health categories, which help connect design quality across multiple products. And Scorecards communicate our progress using a love language already accepted and understood by business partners.

Final Thoughts

When you lead Design, Design is the product. And like any product, it needs to achieve fit within its market and prove it with evidence that the market values. The Four Fits framework provides a systematic approach to do just that.

IME, the design teams that intentionally and consistently calculate (and recalculate) how and where design fits within the business are the ones that execs believe are crucial to company success. They repeatedly deliver new value to customers and the business again and again by adjusting these fits.

The design teams that are considered "optional" are the ones who wait for the company to tell them where they fit. They repeatedly deliver, but not in a way that creates value beyond what the business thinks they're capable of.

The question is, which team will you build?