The road to Design Maturity doesn't start with Design.

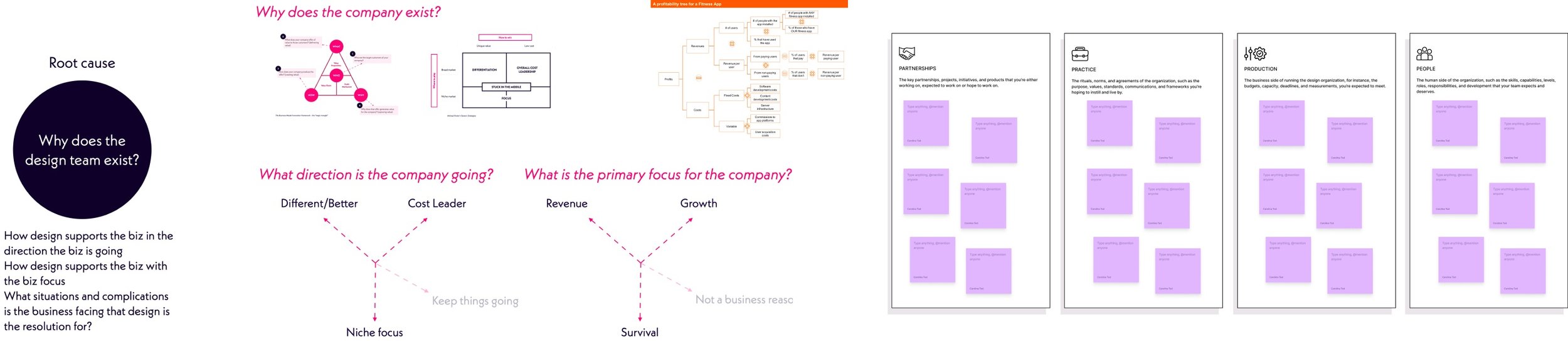

In the introduction to this series, I emphasized that better Design is not the sole factor for figuring out where and how design plays a vital part in a company's success. There are actually five essential elements required to examine the first of these fits, the Model-Practice Fit:

- Understanding the business model.

- Understanding the practice (people, process, operations, budget, etc.)

- Establishing early hypotheses about the fit of the design practice and the business model.

- Understanding the practical implications of achieving Model-Practice Fit in reality, not just in theory.

- Identifying strong indicators of finding Model-Practice Fit.

The wrong way to do it

In 2011, when I joined Electronic Arts (EA) to lead a new team of designers, program managers, and front-end developers, I was also a part of the leadership team for a newly formed organization at EA called the World Wide Customer Experience team. After assembling my team, I recall thinking:

"I can't wait to demonstrate how we can build exceptional products and services because that's what they asked us to do."

Although this mindset may seem reasonable if you have been in a similar position, it is flawed. I assumed that our team was the solution to their problems, essentially putting the cart before the horse.

What I should have done instead is focus on understanding the challenges and needs of my colleagues as they worked towards improving the experience for EA's customers. I made the common mistake of assuming that my colleagues wanted us to decide for them.

This is why I struggle with the term "Design-Led Strategy." While I understand that it refers to a practice and even a philosophical approach, my colleagues often interpreted it as "Everyone Follows the Design Team." Although this interpretation may make sense to some, language matters, and the way we word things impacts our perception and understanding.

A better way to find the Fit between the Business Model and the Design Practice

During my second stint at EA, I joined the IT organization. Our task was to develop a completely new catalog of products and services to support Employee Experience. This experience was akin to running a startup within the company.

Fortunately, I had learned some valuable lessons along the way. Instead of focusing solely on what we would be creating, we shifted our focus to understanding the business model of EA and the IT organization.

We examined four key elements:

- Who: We identified several teams eager to collaborate with us. Understanding the power dynamics and influence that each team had within the company was crucial. We initially focused on conducting experiments that would maximize value without causing significant damage if the experiments went wrong.

- Budget: Each new product had different funding sources. If the budget came from IT, we used a traditional Product Development approach. If the budget came from outside our team, and another department paid for the work, we used a more traditional agency or consulting model. Why? Because we considered this as the first phase to gaining trust with that team before trying to convince them, a fully formed Product Development approach would be the best way.

- Motivations: We assessed whether the teams were trying to assist a specific audience that held significant value and importance to the company.

- Problem: We evaluated whether the problem could be easily addressed from a technical standpoint.

Using these criteria, we discovered an ideal testing ground to determine the fit between the business model and the design practice.

One example of this fit was observed when we partnered with the VP of Talent Acquisition:

- Who: The VP of Talent Acquisition

- Motivations: To attract top talent to EA while reducing employee turnover costs.

- Problem: Candidates had to use multiple systems and tools to communicate with the recruiters, hiring managers, interviewing teams, and IT systems. It was a mess.

- Budget: No direct budget allocation. They relied on IT to cover the expenses, which gave us some leverage to drive the conversation.

Based on these definitions, the team began considering potential solutions. Bill Bendrot, Jesse, and a few others collaborated to create a tool called Interview Sidekick. It marked the initial step towards developing a larger platform that would eventually replace EA's intranet. Despite being the same product with the same underlying architecture, Interview Sidekick was a simple web app that:

- Helped candidates understand what to expect during the interview phase, aiding in a smoother process and allowing candidates to focus on the content.

- Established personalized connections with candidates, with all communications at each step of the process in one place.

- Boosted candidate engagement, fostering a connection to EA's culture and providing insights into working at EA (answering the question "why EA?").

- Differentiated EA's interview process from that of other companies, giving EA a competitive advantage in attracting talent.

Although the app seemed simple, teams within EA had never experienced this type of product before. It helped the Talent team solve business problems and allowed us to adapt our practice to accommodate budgetary constraints, resource limitations, and cost drivers. Even today, some 8 years later, Interview Sidekick remains the standard way new candidates interview at EA.

This brings us to the concept of practice fit. We identified four main elements that were crucial to define:

- Initiatives: The key tasks and activities related to product work that the team was working on, expected to work on, or hoped to work on, such as which development approach, phases, tools, etc.

- Process: The rituals, norms, and agreements of the team developing the product, such as the principles, workflows, communications, and frameworks.

- Resourcing: Identifying and scheduling the exact people who would be part of the product development team

- Capabilities: The key skills, levels, roles, and responsibilities the team provides.

These were the elements we identified:

- Initiatives: Creating the initial v.1 product for Inverview Sidekick, which included scheduling the onsite interview, tips to prepare for the interview, communicating status updates with the candidate, and providing next step instructions post-interview.

- Process: We utilized a Design Sprint approach, a new concept that required early signals of if, how, and where it was working. We developed the product over three months using two-week sprints.

- Resourcing: The initial work was done “off-budget”, meaning we found resource availability to create an MVP in 5 days without proposing a formal budget. The goal was to get enough signals from the MVP to become part of the business case to fund the full product development.

- Capabilities: Front-end engineer, Sr. Designer with a Master's in HCI, software architect, project manager, Sr. Recruiter, and QA tester.

These hypotheses play a crucial role and will be explored further in future posts of this series as they inform and deeply impact the other components of the framework: Partnerships and Positioning.

The Realities of Finding Business Model - Design Practice Fit

The reality is that finding Model-Practice Fit is rarely straightforward.

It often takes multiple iterations to identify a fit that works. The process begins with understanding the business model and strategy, not by prioritizing the business aspect, but rather as a reference for the signals that those with a business-first mindset are seeking. This iterative cycle involves creating an initial version of your practice, identifying who benefits from it, and then refining both the model and the practice. It is an ongoing process that becomes easier to comprehend over time.

The same applied to our work on Interview Sidekick. We initially laid out our hypotheses, but as we delved deeper, we discovered that our practice was delivering value to various aspects of the business. We achieved significant wins in enhancing IT's reputation, staying on budget, increasing top candidate closure rates, and improving NPS.

Upon realizing these outcomes, we refined the category, the target audience, the problem, and the motivations based on our actual observations. The second version looked like this:

- Who: VPs running operational, cost-center teams who 1.) owned a budget and 2.) were struggling to solve their problems at scale. HR, Sales, Accounting, Customer Support, DevOps, etc.

- Motivations: To increase productivity while maintaining relative costs, and be seen as change-makers within the organization.

- Problem: Members of their teams were used to consumer grade applications and software. When their tools and apps were slowing them down or causing high frustration, they’d use outside, third-party tools to get their job done - creating security and legal risks.

- Budget: No direct budget allocation. They relied on IT to cover the expenses, which gave us some leverage to drive the conversation.

We saw these teams as early-adopters/testers. We could introduce new ways of working, digital solutions, and have discretion over the approach. When these tests went well, they became case studies to scale our approach to other teams.

The refinement did not stop there. About a year later, we experienced another major shift, which I will discuss in future posts.

Model-Practice Fit is Not Binary

The iterative cycle of Model-Practice Fit leads us to another important point:

Model-Practice Fit is not a binary concept, nor is it determined at a single point in time. A more accurate way to perceive Model-Practice Fit is as a spectrum ranging from weak to strong.

When thinking about Model-Practice Fit as a binary concept, it implies that the business model and design practice remain static. However, in the real world, change is constant. Therefore, we should consider changes to the business model as the focal point for altering our practice.

In my career, I’ve seen three primary ways in which the business model changes:

- Senior Leadership turnover

- Regulatory pressure

- Overall business evolution

The first two changes happen quickly, without much notice, and we can only respond when they happen. The third one though, is a longer process that Design Leaders can play a more proactive role in influencing, but are never the sole party responsible for the change.

Signals of Model-Practice Fit

If Model-Practice Fit is not binary, how can we determine if we have achieved it? While there has been some discussion on this topic, most of it does not reflect reality.

In almost every case, it is necessary to combine qualitative and quantitative measurements with your own intuition to understand the strength of Model-Practice Fit. Relying on just one of these areas is akin to trying to perceive the full picture of an object with only a one-dimensional view.

So, how do we combine qualitative, quantitative, and intuitive indicators to gauge the strength of Model-Practice Fit?

1. Qualitative:

Qualitative indicators are typically the starting point for measuring Model-Practice Fit, as they are easy to implement and require minimal customer feedback and data.

- Employee Satisfaction

- Partner Satisfaction

- Team Health Scores

To gain a qualitative understanding, I prefer using Net Promoter Score (NPS). If you are genuinely solving the audience's problem, they should be willing to recommend your product to others.

The main downside of qualitative information (compared to quantitative data) is that it is more likely to generate false positives, so it should be interpreted with caution.

2. Quantitative:

There were three initial quantitative measures to understand Model-Practice Fit: Budget Adherence and Utilization.

- Budget adherence

- Velocity

- LOE Accuracy

You’ll notice here, that we’re not talking about Product-Market Fit. That’s work that was done within the Product Team. Model-Practice Fit is ensuring that the resources, processes, and skills within the design team are fitting to the business needs.

3. Intuition:

Intuition is a gut feeling that is difficult to articulate. It is challenging to intuitively understand whether Model-Practice Fit has been achieved unless you have experienced situations where it was absent and situations where it was present.

Here’s a vibe that time and time again has shown me that Model-Practice Fit is strong:

When you have strong Model-Practice Fit, it feels like stakeholders are pulling you forward into their decision-making meetings rather than you pushing yourself into them.

The Key, Practical Points to Help You Find Model-Practice Fit

If you haven’t noticed yet, many of the things we teach here are structured activities to gain new insights into how you can learn to find your four fits.

The key questions that it’s important to have answers for are:

- How does design support or enhance the business in the direction it’s going?

- How does design support or enhance the current focus on the business?

- What challenges is the business facing that the design practice is THE ideal solution?